Classic Collisions of Cars and Celluloid

Films made in the '70s are quite often imbued with a sensibility that is more visceral than intellectual, and are often blessed with a simplicity lacking from today's films. Three classic '70s films are also three classic car movies: VANISHING POINT (1971), CRAZY MARY, DIRTY LARRY (1974), and THE DRIVER (1978). None of these films are CITIZEN KANE, by any means, but they never attempted to be. CITIZEN KANE is a brilliant classic that set a million different standards and high watermarks. The three aforementioned car movies are highly entertaining, well-made excuses to tear-ass around in high-performance cars. VANISHING POINT (directed by Richard C. Sarafian) even worked in an excuse to have a totally nude beautiful blonde riding around the desert on a motorcycle.

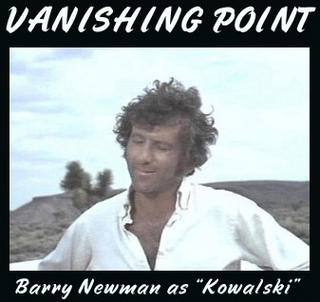

The plot for VANISHING POINT is simplicity defined. Barry Newman plays Kowalski, a driver for a car delivery service. He agrees to drive a supercharged 1970 Dodge Challenger from

Barry Newman’s main co-star, however, is the desert plateau that provides the backdrop. The sun, the heat, the sand, and the sheer vastness are all components. There’s literally nothing between him and the pursuing cops besides speed, distance, and driving prowess. The cops seemed determined, but Newman is even more so. He picks up a couple of hitchhikers and meets a couple of desert drifters along the way (including an always memorable Dean Jagger), but it’s all about the speed, the bet, and the total absence of respect for anything published by the DMV. And as cool as the ending is for the viewer (I won’t spoil it for those who haven’t seen it yet), it’s a definite bummer for whoever was expecting the Dodge Challenger in Frisco.

The plot for DIRTY MARY, CRAZY LARRY (directed by John Hough) is just as simple, though not simplistic. Under threat of holding the wife and daughter of a grocery store owner/manager hostage, Crazy Larry Rayder (Peter Fonda) and “ace mechanic” Deke Sommers (played by Adam Roarke, who looks a lot like CNN’s Aaron Brown) high-tail it with the ransom. (The grocery store owner, incidentally, is played by Roddy McDowell, who receives no screen credit.) The starring vehicle in this one is a Dodge Charger, and in the backseat is Dirty Mary Coombs (Susan George), who shared Larry’s bed the night before. She tags along for the ride, providing a nice balance between rebel-for-the-hell-of-it Larry and hard-boiled realist Deke. The chemistry between the three characters fuels the film as much as the race to the finish-line does, and that’s what Larry considers the heist and run from the law to be: a race. Once they hit the road, the money seems to be of little consequence.

Vic Morrow plays Sheriff Everett Franklin. In his pursuit of the high-speed lawbreakers, Sheriff Franklin proves to be cut from very much the same cloth as Fonda and crew. Refusing to wear a badge or a uniform, he doesn’t even carry a gun. All that matters is getting the job done, and watching Vic Morrow play the rebellious cop to Fonda’s anti-establishment thief is a match made in cinematic heaven.

Vic Morrow plays Sheriff Everett Franklin. In his pursuit of the high-speed lawbreakers, Sheriff Franklin proves to be cut from very much the same cloth as Fonda and crew. Refusing to wear a badge or a uniform, he doesn’t even carry a gun. All that matters is getting the job done, and watching Vic Morrow play the rebellious cop to Fonda’s anti-establishment thief is a match made in cinematic heaven.

The ending is one of my favorite endings to any film. Quoting a review of the film on DVD Verdict, “the ending truly vaults this film above just another action movie into something truly original.” Even more intriguing is Dirty Mary’s last line in the film, which borders on premonition.

Though distinguished by good acting and exceptional direction, VANISHING POINT and DIRTY MARY, CRAZY LARRY are largely feature-length chase scenes punctuated with moments of memorable character interaction. THE DRIVER, however – written and directed by Walter Hill – follows the classic noir formula of the lone man trapped within a multi-layered web of deceit. Rich with all the sounds and textures that so embody the best of ‘70s filmmaking, THE DRIVER stands as an example of how to layer a film with complexities without undermining its simplicity.

In this highly-stylized and under-rated modern crime drama, things are so reduced to their base elements that none of the characters have names. The characters reflect archetypes so familiar to noir that one can instinctively fill in the blanks as to where they fit in and what makes them tick. All necessary information pursuant to the plot is telegraphed via a modicum of dialogue.

O’Neal’s character is a true enigma. The most that we ever find out about him is that he takes shit from no one. He says he doesn’t like guns, but that doesn’t mean he isn’t willing to use one. He makes tens of thousands of dollars as a fairly selective driver-for-hire, yet he lives in a bare-bulb room in a shabby boarding house. When he’s actually in his room, he does absolutely nothing. While hiding out briefly in an equally rat-infested hotel, he turns on a small AM Radio, but generally he just lies on his bed, fully dressed, ready to spring. It’s evident from the beginning, however, that he knows how to drive a car. The chase scene that lights the film’s fuse is tightly choreographed and demonstrates his ability to successfully elude no fewer than six police cars, skillfully causing them to crash and burn one after the other.

Bruce Dern plays The Detective, with two plainclothesmen under his command. Dern plays the part of the prick cop to perfection; he’s never been better. Constantly needling his subordinates and forever bragging about how he’s going to catch “the cowboy who’s never been caught,” he’s nothing if not an asshole.

Isabelle Adjani is cast as The Player. She’s as much a loner as The Driver is, but we learn that she’s living on the generosity of someone who pays her rent and stops by a couple of times a month. She’s the only witness who can identify The Driver to the police, but doesn’t – for a price. (Apparently a deleted scene gives greater insight to her character, but to be honest, my copy of this film is on VHS, and I should mention that the VHS version is 131 minutes while the DVD version is only 91 minutes. Supposedly the longer version has more car chases.)

When The Player fails to identify The Driver, The Detective concocts a scheme in which a couple of would-be supermarket thieves (another supermarket heist!) are to hire The Driver for a bank job. The Driver is none-too-eager to bite and takes an instant dislike to one of the thieves, quite possibly for questioning his skills. The Driver shows just how well he can drive in an amazing parking garage scene in which he proceeds to demolish their orange Mercedes and most certainly give them all whiplash.

Some viewers have criticized the actors for being stiff and expressionless, but it’s this focused, never-take-your-eye-off- the-ball approach that keeps the film rooted in its noir origins. THE DRIVER begins tense and clenched and never loosens its grip. Only Dern ever cracks a smile, but that’s only because he’s so smug he can barely stand himself.

The ‘70s was a period of American filmmaking that will never be repeated. And while there are certainly other ‘70s films that indulge the undeniable appeal of a good car chase, these three films make it their mission.